Background and Context

Some of the work involving Centric over the last 18 months has revealed there are huge issues in how local authorities engage with communities.

Residents bemoan the fact there is poor communication and a dearth in knowledge about the activities in which local authorities are involved in. Plus, staff don’t meet residents to understand first-hand trends, concerns and dynamics.

Growing up in inner-city Leicester during the 1980s was enriching in terms of community and anti-colonial thought, despite the political climate of the day typified by the Thatcherite years and jingoistic-nationalist fervour inspired by the Falklands War. It was a thriving hub of activism, black globality (Connell, 2019), shadow economies, subcultures and, importantly, community spirit.

From this era, there was already the formation of an ‘urban intelligentsia’ compounded by interacting with other people from the black globality and mingling with people of requisite cultural capital who had arrived due to gentrification. Access to knowledge with the internet was central to that too. Hence, at present many people in such communities no longer feel they are merely third or second-tier.

In this sense, there’s been an uprising and a move away from hedonistic consumerism towards various forms of activism, along with people no longer relying on state and governmental services. For instance, the chicken shop used to be the prime location for the urban locale – but then many people became vegan!

To better engage with communities in light of these dynamics, we have formulated the Seven Rules for Highly Effective Community Engagement:

Rule One - Community Leadership

Often the best community leaders are those who may clash with institutions and do not always see eye-to-eye with the structures and status quo of institutions.

Rule Two - A ‘Cultural Mediative’ approach

Centric’s co-design approach harnesses African-originated inclusive decision-making and resolution approaches. These are rooted in ancestral conflict resolution processes that are still relevant to the modern urban locale where offstage and hidden transcripts abound. Powell-Bennett states (2017: 105):

In some African tribes and ethnic groups, mediators are family or community elders freely chosen by each party, who play a strictly neutral role (Sone, 2016: 54). In these groups, mediators listen to each party’s side and encourage them to also actively listen, understand and appreciate the perspectives and interests of the other party. The mediators facilitate a process to enable all to find a solution that is satisfactory, without imposing a solution and sharing power – this African-centred approach is harnessed in Centric through its co-design ethos.

Hence, this approach has buy-in from sections that are either distrustful of dominant institutions or disconnected from Eurocentric organisational structures that are often colonial, paternalistic, patronising and authoritarian. African mediation is more active and includes making recommendations, assessments, conveying suggestions, reviewing agreements, revising etc. (Ajayi and Buhari, 2014: 150).

Clinical, colonial and authoritarian approaches to research and co-design are not trusted by many people in the urban locale as they lack relationship equity which is a feature of mediation systems originating in Africa. This means Centric mediation is also a sought-after aim, where necessary, in cases where research participants indicate problems with dominant institutions or structures. This Cultural Mediative approach is part of Centric’s co-design ethos to develop equitable interventions and solutions.

Hence, Centric’s interview and focus group research phases are not merely qualitative research for research’s sake, but also incorporate mediation aiming to work towards improvements and changes whenever possible.

Rule Three - Understanding, and conceding to the presence of, the Distrust-Apathy Nexus

Local authorities can often damage relationships with sections of their communities if there is a sense there is no avenue for consultation, little recourse for feedback and when there is a general feeling locals are being held in contempt in lieu of the ideas of ‘experts‘. Deferring to expertise thinking is of course, always necessary, but it should have an equal seat around the table alongside local community knowledge and lived experience to ensure there is not an imbalance of power.

This is even more significant regarding health-related interventions, behaviour change and public health strategy. The lack of local community knowledge can, in some instances, reinforce the current crisis of epistemic trust (Goldenberg, 2021).

This current crisis of trust is also a challenge facing public health as they too succumb to the wider societal trend of distrust of government (Hardin, 2004), politics (Claude and Hawkes, 2020), science and media (Birkhead et al., 2022: 269; Warner and Lightfoot, 2014: 452; Stoto et al., 1996: 11). Also, narratives of distrust towards government have roots in the liberal political theory of Hume, Madison and Locke as distrust and cynicism towards governments was deemed to be the default setting of the thinking citizen. The notion of ‘liberal distrust’ (Hardin, 2004: 4).

This distrust is not merely on account of the ‘scientific expertise of a particular country not being recognised’, which was suggested by Meyer (2016: 449). As where there is a lack of trust in government, there will also be a lack of trust in local authorities and associated government-supported public health initiatives; this has been seen in parts of West Africa where civil wars and violence led to a lack of trust in government institutions (Richardson, 2020: 53).

Hence, the onus is also upon medical institutions to also be aware of distrust, cynicism and scepticism which they may encounter when out in the communities and in the field (Cohen, 1991; Mays and Jackson, 1991 and El-Sadr and Capps, 1992).

Moreover, contrary to Meyer (2016: 449), Richardson (2020: 5) suggests there is an “epidemic” of coloniality of knowledge production within “the mechanisms in public health science - in particular, epidemiology - that enable groups to sanction one account of disease causation over another”.

Tangible reasons for the mistrust amongst many black communities can possibly be traced back to morally and ethically questionable instances where black and minority ethnic people were abused through medical research and unethical experimentation (Smedley et al., 2003: 131). This has been discussed by medical ethicist Washington (2006), who has discussed the role of James Marion Sims, regarded as the ‘father of gynaecology’. Hence, Washington has noted (2015) that “it is not merely about conspiracy theory, but conspiracy fact” when discussing the tangible reasons as to why black communities may not trust health and medical services and systems.

Deep-seated mistrust in public health and medical institutions among black communities has been prevalent for over 50 years (Brandt, 1978; Olson et al., 1988; Hall et al., 1991; Blanchard, 1999; Corbie-Smith et al., 2003; Washington, 2006; Jamison et al., 2019).

In 1984, fifty-two thousand African-American women were screened for sickle-cell anaemia and over a quarter of them were screened without their knowledge or consent and as a result, neither received the potential benefits of the screening nor gained any education or guidance regarding the condition (Dula et al., 1993: 187). In 1988, Olson et al. had noted that distrust of health professionals may limit the outreach of public health organisations which do not collaborate with trusted community institutions.

Ball and Strekalova (2020: 219) also noted that deficiencies in the delivery of mental health services within black communities can also instil medical mistrust. Misdiagnoses are less likely to occur and communication is more efficient when there is cultural representation in the profession, along with a comprehension of the cultural context of the patient.

There is distrust of traditional means of addressing public health issues, and for some time, public health authorities and officials took for granted levels of public compliance (de Waal, 2021). Hence, the old adage of “trust me, I’m a doctor” will no longer wash.

De Waal states:

Minorities and formerly colonised peoples have had good reasons to distrust the official health apparatus, which too often treated them with contempt.

De Waal also stated that Western publics are growing suspicious of medical authorities (De Waal, 2021). Greenberg et al. (2015: 82) concede that the “legacy of distrust that exists between minority populations and the medical community is an undeniable consequence of historical experimentation on certain groups.” Mistrust and fear of healthcare systems can lead to barriers in accessing services and care, thereby exacerbating health disparities.Yet, there can also be distrust on the part of public health officials of politicians when it comes to population health (Gostin and Stone, 2007: 66).

Rule Four - Communication strategies to rebuild trust

Heller and Wyman (2019: 259-260) note that any efforts to promote community change are increased when the beneficiaries and recipients of the project trust and respect the people who are actively involved in promoting any new behaviours. Hence, community workers who have a rapport with people in communities can facilitate health communication and behaviour change. Where communication is lacking, this is often a cause of community distrust (Beaton, 2006: 54). Alelezam (2021: 160) notes that public health professionals and clinicians should:

aim to take responsibility for past actions, make amends and regain trust within these communities. It is essential that public health professionals work with communities to assess their needs and desires concerning health. Working closely with communities to understand and right past harms may help to improve relationships with communities in the future. Dismantling systems of oppression in society will go hand-in-hand with community engagement. Additionally, ensuring that healthcare professionals and public health researchers are trained in inclusive and anti-racist practices will ensure a more appropriate workforce that is attuned to the needs of individual communities.

Alelezam also highlights the significance of forms of community research to better engage communities in productive ways and particularly when it comes to issues around public health. Buchanan (2019: 345) suggested communities should also play a role in deciding on policies which impact them, particularly where there are higher potentials for harm. Indeed, threats to public health and to climate change for instance have major adverse effects on the most vulnerable communities. Buchanan has highlighted (2008: 15-21) that increased autonomy for communities results in better health and hence when communities are empowered to take care of themselves and those around them, this is more just the process rather than paternalistic dictates issued from distant authorities.

Hence, there must be a clear communication strategy where affected communities are involved. Saunders et al. (2013: 156) state:

It is not enough to simply make information available for use by the public. When conducting investigations, involving the community must be an integral part of the process and should be planned for.

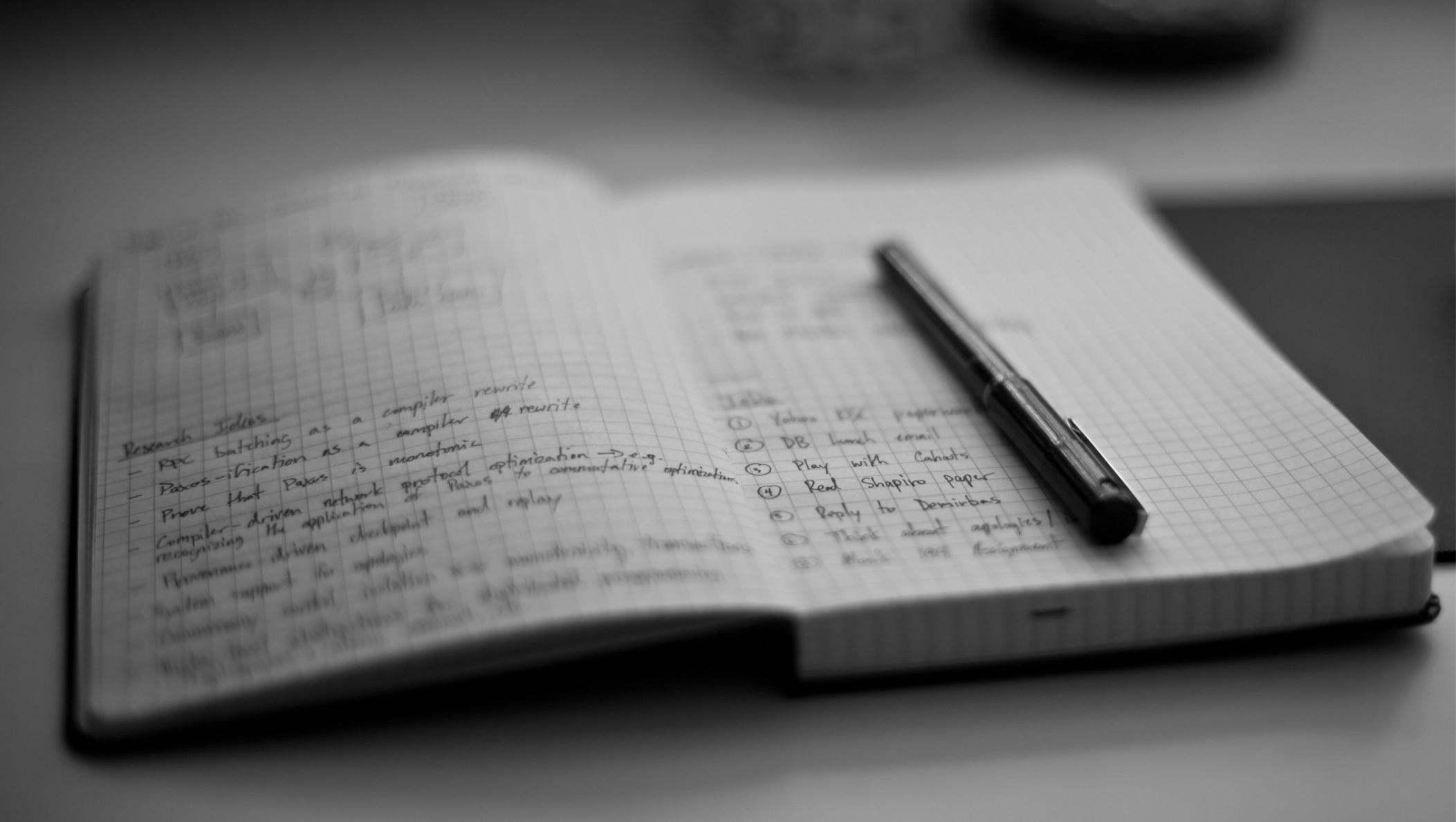

Therefore, council officers also need to get out of the office and tour the locales in which they work and around which their work is based. This is even more relevant given the fact their work is supposed to be all based around serving the very communities in which they work.

Officers and officials, therefore, need to understand some of the realities of daily living and day-to-day life. The landscape is changing.

Rule Five - For public health strategies, community engagement is key

Community engagement is emergent as a key facet in implementing and developing public health interventions. Moreover, in emergency situations such as pandemics, there is a greater need for local authorities to develop communication in ways which maximise positive behavioural responses from populations (Thompson et al., 2022: 1035).

Community members can take on roles including participating in consultation processes, collaborating or leading on the design, delivery and evaluation of public health strategies. A report in 2009 by Herbertson et al articulated the following checklist for effective community engagement:

With engagement, it is important to avoid a myriad of pitfalls, which have been highlighted by Birley (2011: 139). Firstly, promises which cannot be kept should not be made. Secondly, care should be taken to avoid biases. Thirdly, all groups should be represented. Fourthly, medical professionals should be part of any engagement.

Rule Six - Relevant approach to engagement

The right balance, format and energy is also required to retain, excite and activate communities. Hence, the format pertinent to the community one is trying to engage must be gauged appropriately.

Connected to this is the fact the language used to engage communities is also not graded appropriately or in a manner easily accessible to many people within communities. “You need a degree to understand this stuff” is but one of the answers heard from communities by some of the Centric team.

Institutions also do not tap into the mediums which are available when it comes to recruitment and employment with them, hence missing out on engaging a large swath of youth.

Rule Seven - Various nuances to be understood

There is not a one-size fits all, as we will soon be discussing in forthcoming work on the ‘black identity-culture nexus’.

Data is being collected but it is not necessarily being interpreted in a nuanced manner which takes into consideration issues which fall below the radar.

-----------

* “Another reason why African American respondents’ willingness to use mediation showed a high frequency may have been due to their African ancestors’ traditional tendency to use a third-party intervention such as elders in their community.”

References

Hover and click to download

COPYRIGHT 2021. CENTRIC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED